History of "Joshi", Japanese All-Female Pro Wrestling

Have you ever wondered why Japanese All-Female Pro-Wrestling—known as Joshi Pro-resu in Japanese, or just “Joshi” to fans around the world—has thrived in Japan like nowhere else?

It’s a phenomenon unique to the country of Japan: dozens of all-women promotions, hundreds of dedicated female wrestlers, and live events that regularly pull in thousands of paying fans. No other country has come close to matching the scale, popularity, or cultural relevance of Joshi.

Why is that?

Some chalk it up to Japan’s deep-rooted love for dramatic, larger-than-life performance, just like the centuries-old art of Kabuki. Many people see Joshi as a real-life extension of manga and anime heroines—fierce, flashy, and full of heart. There’s also the argument that Joshi provided a cathartic outlet for Japanese women during times of male-dominated societal stress: watching strong women fight and win is incredibly empowering.

While those reasons surely played a role, we’d argue the core reason Joshi flourishing is the same reason baseball flourished in Japan: simply put, they were great players. Talented, magnetic, unforgettable women who made Joshi unmissable.

To understand just how this all began, let’s take a quick dive into the roots of Japanese women’s pro wrestling.

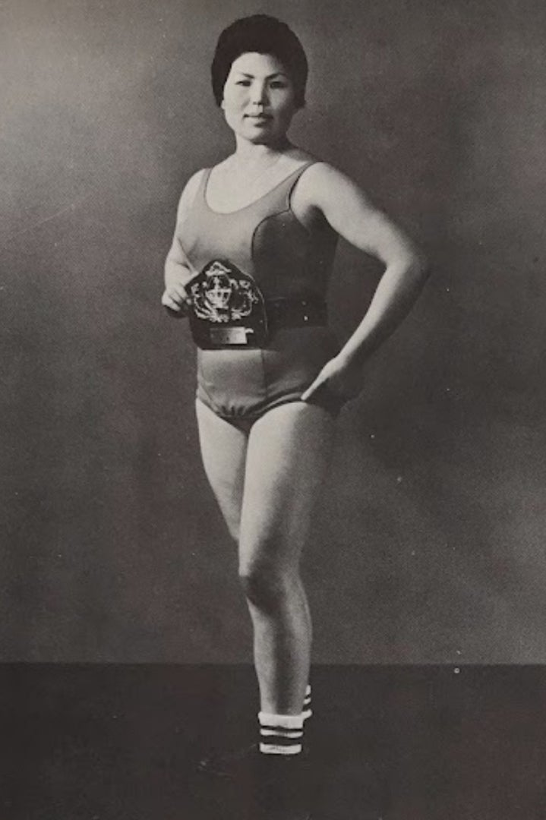

Part 1: The 1940s–50s — Origins of a Movement

It all started with one fierce young woman: Sadako Igari, better known by her ring name Lily Igari, who debuted in 1948 and is widely regarded as Japan’s first female professional wrestler. The youngest of eight siblings—and the only girl—Sadako grew up tough, scrapping with her seven older brothers. It wasn’t just sibling rivalry that shaped her. Post-WWII Japan was a land of scarcity, and at just 16, Sadako found herself performing in “fighting shows” alongside her brothers to entertain American occupation troops.

The soldiers loved it—especially seeing a teenage girl knock men flat on their backs. And Sadako? She loved it too. But not everyone did. She faced harsh criticism and even violence, once having a glass milk bottle thrown at her head by an angry audience member. Still, she stood firm. “I felt no shame in doing what I truly liked to do,” she would say years later.

The real turning point came in 1954, when two American legends—Mildred Burke and Johnnie Mae Young—toured Japan, showcasing women's pro wrestling at a professional level never seen before. Their visit helped spark new interest and set a blueprint for what Joshi could become.

Just a year later, in 1955, Japan held its first national women’s wrestling championship in Tokyo. Sadako Igari entered, dominated every match, and walked away as the first-ever Joshi champion.

And the best part? Sadako Igari is still alive today—at 92 years old, living in Tokyo, and reportedly still packing a punch.

This is the: "Tokyo Pan Trio"

(Picture sourced from "Kobe Shinbun" 2023/7/13)

Sadako Igari (92) Is Still Fighting Strong!

(Picture sourced from "Kobe Shinbun" 2023/7/13)

Part 2: Breaking Barriers and Building Icons (1960s–1970s)

After the experimental beginnings of women’s pro wrestling in Japan during the 1940s and 50s, the 1960s and 1970s became a make-or-break era for joshi Puroresu. These decades were marked by collapse and reinvention—paved by scandals, saved by innovation, and ultimately transformed by the rise of pop-culture icons.

From Chaos to Crisis

By the early 1960s, women's professional wrestling in Japan was gaining visibility—but the infrastructure was still deeply flawed. Promotions lacked regulation and professionalism, and wrestlers were often minors subjected to harsh training and poor treatment.

One infamous incident involved promoters taking young girls on wrestling tours without proper guardianship, leading to public outrage when a 15-year-old wrestler was found to be traveling and performing in harsh conditions without parental consent. Incidents like this fueled criticism from media and civic groups, casting a shadow over the entire industry.

As scandals mounted, and media pressure intensified, the women’s wrestling scene began to disintegrate. Television networks withdrew support. Promoters folded. By the mid-60s, Joshi Puroresu had nearly vanished from the public eye.

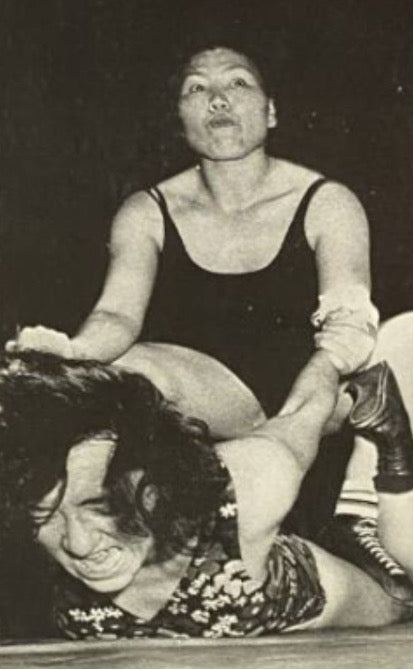

Yukiko Tomoe: A Star in the Shadows

Even during this turbulent period, one figure stood out: Yukiko Tomoe. Known for her graceful style and quiet strength, Tomoe became the first Japanese woman to gain international recognition. In a landmark moment in 1968, Yukiko Tomoe defeated Fabulous Moolah in Japan to capture the NWA World Women's Championship—a title controlled by the U.S.-based National Wrestling Alliance (NWA).

Though Moolah would later reclaim the belt in the U.S., Tomoe’s victory was symbolically powerful. It showed that Japanese women could stand toe-to-toe with the most established global stars and win. She became a beacon during a dark time for the sport.

Yukiko Tomoe

(Sourced from 1968 pamphlet titled “GIRL WRESTLING INTERNATIONAL CHAMPION MATCH”)

Yukiko vs Fabulous Moolah (Or could be Bette Boucher)

(Sourced https://ameblo.jp/kimumasa992/entry-12884617234.html)

The Rebirth: Zenjo Rises

That same year, 1968, marked the beginning of a new era. The Matsunaga brothers founded All Japan Women’s Pro-Wrestling, or Zenjo (全女). They took lessons from the failures of past promotions and implemented strict guidelines: early curfews, no dating, intensive physical training, and a mandatory retirement age of 25. Wrestlers were trained not only as fighters but as idols who would appeal to the public’s sense of morality and entertainment.

Zenjo also targeted television, understanding its power to build nationwide audiences. By the early 1970s, women’s wrestling was back on TV and gaining traction—especially with younger viewers.

Foundations Before Fame

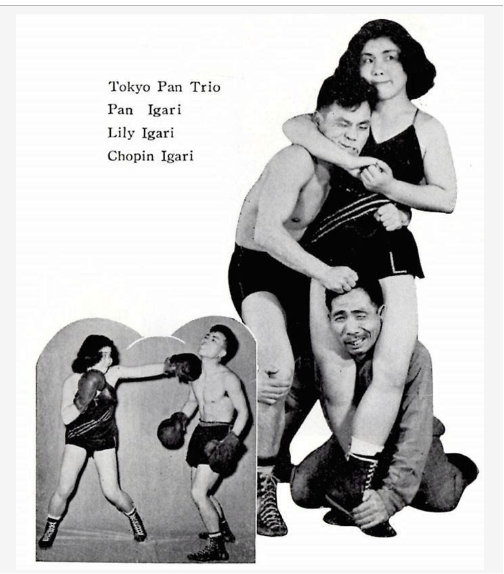

Before the pop sensation era exploded, wrestlers like Aiko Kyo, Jumbo Miyamoto, Mach Fumiake helped lay the foundation of Zenjo’s success. These early stars performed in local halls and on small TV spots, steadily building credibility for the revived sport. Their wrestling style began to evolve into a faster-paced, martial arts–inspired form that would later define Joshi Puroresu.

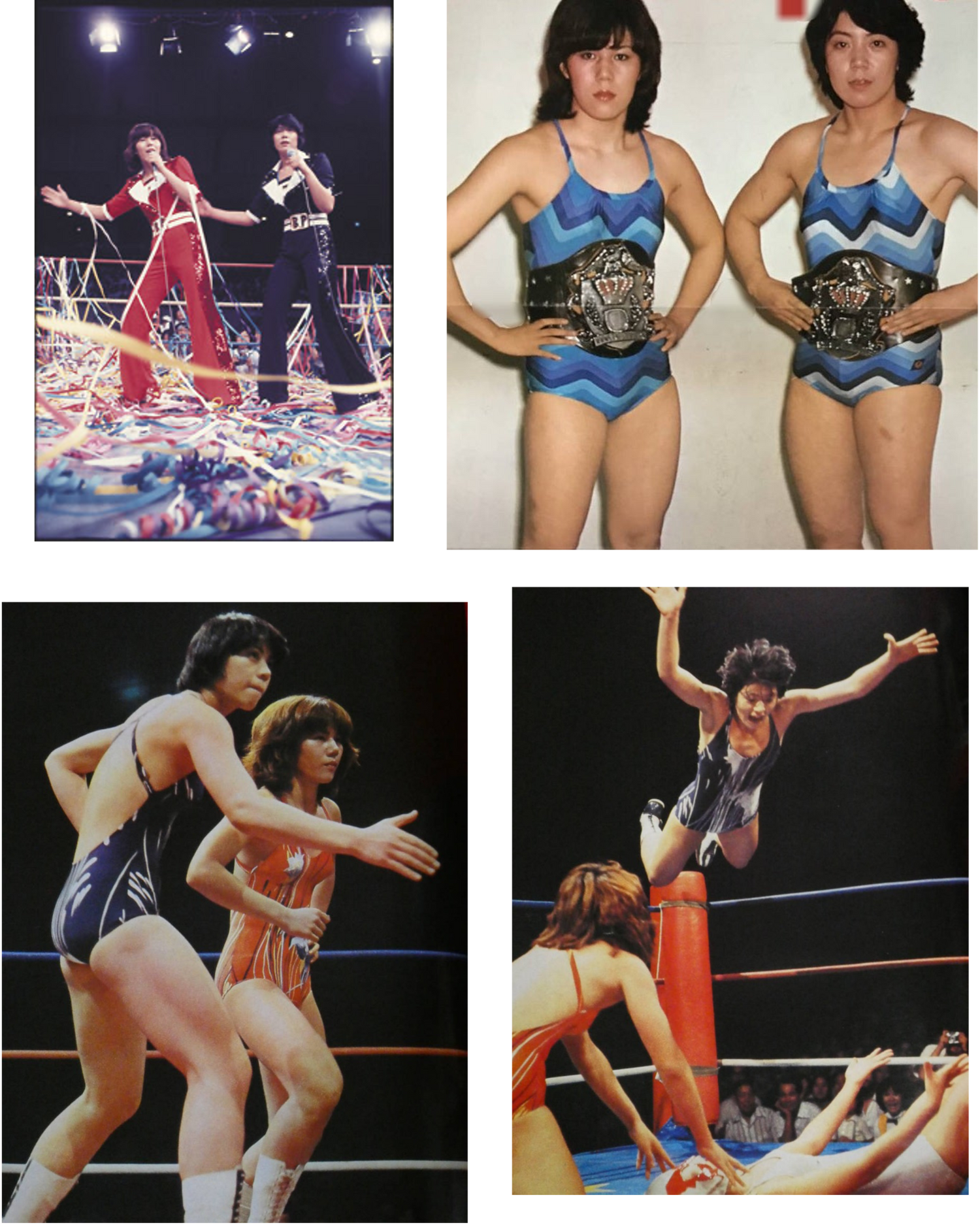

The Beauty Pair: The Game Changer

The true breakthrough came in 1976 with the debut of the Beauty Pair: Jackie Sato and Maki Ueda. With their matching outfits, coordinated entrances, and undeniable charisma, they were marketed not only as elite athletes, but as sparkling teen idols. And crucially, their main fanbase wasn't older men—it was young Japanese girls, who saw them as glamorous, relatable, and source of inspiration.

Their popularity went beyond the ring. The Beauty Pair released singles, starred in photo books, movie, and made regular appearances on TV. Their hit song, "Kakemeguru Seishun" ("Racing Through Youth"), became an anthem for adolescent girls—combining the themes of friendship, youth, and ambition with the rebellious energy of wrestling.

In the ring, they battled rivals like the Black Pair in high-drama matches that combined athleticism with theatrical storytelling. Their presence made Joshi wrestling a pop culture phenomenon for the first time.

A Blueprint for the Future

By the end of the 1970s, Zenjo had laid the structural and cultural groundwork for what would become Joshi Puroresu’s golden age. With a functioning dojo system, mainstream visibility, and seemingly unlimited recruits of young, athletic girls from all over Japan, the sport had evolved into a unique blend of combat, idol culture, and televised entertainment.

To Be Continued…

In the 1980s, a new generation of athletes would take Joshi Puroresu to unprecedented heights—pushing in-ring innovation, emotion, and popularity even further. But none of it would have been possible without the pioneers, idols, and survivors of the 1960s and 1970s.